Studying medieval texts means, of course, reading them in manuscript form, if they have not been edited. And that is the case of most of the texts produced in the Middle Ages, although in some fields generations of scholars have prepared careful editions of the most important texts. However, some contemporary scholars limit their sources to the printed editions, at the same time limiting themselves to quote always the same authors.

Medieval philosophy is a relatively well doted field of study, because previous scholars have provided us with good editions of many sources. Even so, this is not enough if one wants to study the various works of an author (for instance the works of Robert Kilwardby or Jean de Jandun), or if one wants to research the tradition of a specific text, for instance the tradition of the De anima during the Middle Ages.

Thus, palaeography and codicology are necessary disciplines for a scholar working in any field of medieval studies. However, manuscripts can also tell us much more than the texts they contain. The material object of a manuscript is a rich and exciting experience for anyone who has the chance to take one in his hands (which is more and more difficult today, because of the increasing number of scholars and the increasing carefulness of manuscript keepers). The volume with its parchment or paper leaves, their dimensions, the composition of the quires, the ruling of the page, all these elements can teach us something about the time and place in which the texts have been written, about the origin and history of the codex, about the environment in which the texts were composed, etc.

A modest university book

Describing a manuscript almost always produces interesting discoveries. As a contribution to the volume in honour of François Dolbeau, a discoverer of many texts (including sermons by Augustine), I undertook the description of a modest manuscript, one of those collections of university books that are present in every library, but generally unstudied unless they contain one or two texts of famous authors. The article, entitled “Textes connus et inconnus: un recueil universitaire du XIVe siècle” (2013, see List of publications, Art. 69) concerns a manuscript kept at the university library of Montpellier (Bibliothèque universitaire, Méd. 293), which formerly belonged to the library of Clairvaux. Here is the description in the catalogue:

Ex libris (f. 170vb) : « Iste liber pertinet ecclesie Clarevallis, Quicumque furatus fuerit, restituat », et cote XVe s. « V 22 ». Bibliothèque du dortoir, XVIe siècle, f. 1v : « Liber sancte Marie Clarevallis » et cotes : vic xxx ; viiclxx. Etiquettes superposées, collées au second plat, dont la plus récente porte le titre : « Questiones philosophie naturalis. <C h>iii ».

It is a rather messy, at first sight unappealing manuscript, composed of three distinct parts (seventeen quires in total), containing philosophical texts copied by various scribes, mainly English. It assembles numerous texts, known and unknown, often unfinished, particularly commentaries on Aristotle’s Physics and Metaphysics, De generatione et corruptione, some Questiones De celo, and various notes which seem to point to a theologian as the owner. The manuscript may have been constituted by an ‘abbas Cisterciensis’ of English origin, desiring to keep some material traces of his education at the faculty of arts. As the commentary on the De generatione seems to be unknown, I added in appendix a list of the questions. The conclusion is evident: many texts still sleeping in this kind of manuscripts (and they are numerous indeed) remain to be discovered.

The handling of this kind of volumes, tools for study that have been in the hands of various medieval scholars, is an exciting experience. One has to find how this particular volume works, how the owner found his way in it, how it remained useful for him, even after leaving the faculty of arts.

The making of texts

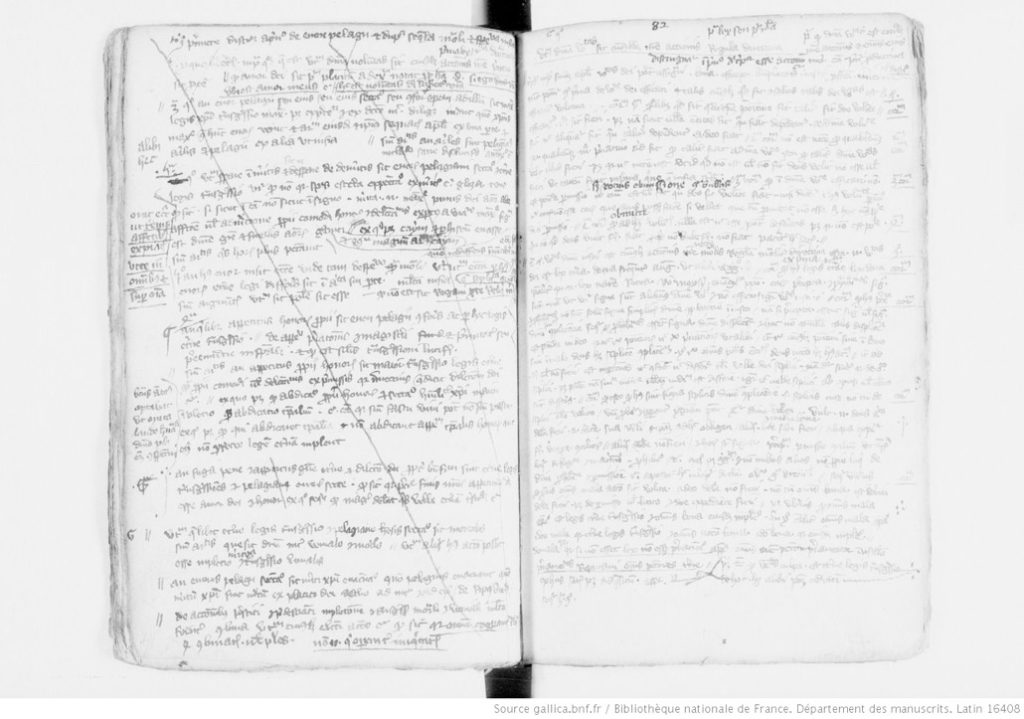

A double page of the manuscript Paris, BnF lat. 16408

The study of manuscripts also reveals other features of the making of texts, for instance the way in which they were written and rewritten, in order to establish the final version. In this context, I contributed an article to a volume in honour of Colette Sirat entitled Ecriture et réécriture dans les textes philosophiques médiévaux (2007). The title of my contribution: Les raisons de la réécriture dans les textes universitaires : quelques exemples (see List of publications, art. 56) is of course rather vague. The first part concerns philosophical commentaries, the second part, more original, studies several versions of a questio de aula, part of the examination in the faculty of theology. This question has been transmitted in three versions. I quote:

La version C ressemble en effet à une mise au net des matières des versions A et B, probablement avec l’insertion des arguments entendus durant la discussion et notés à la suite du résumé de la version B, mais avec l’exclusion de tout ce qui se réfère à un contexte cérémoniel. On a l’impression que l’auteur a voulu avoir une description propre et complète de la façon dont on pouvait traiter cette question en trois conclusiones avec leur corollaria, une description qui pouvait servir à d’autres occasions. Son intention n’était pas de garder la trace de l’ensemble de la dispute, car les trois versions n’en donnent nulle part le rapport complet. Ce qui l’intéressait manifestement, c’est la position qu’un bachelier pouvait formuler à propos de cette question.

On a donc ici deux cas de réécriture : le résumé (partiel) d’un texte qui est probablement une reportatio, et la mise au net de la partie centrale et principale de la première partie (la positio) de la dispute qui était à l’origine.

The examination of the manuscripts and their mutual relationship reveals the history of the text:

Comment se représenter le rapport entre les manuscrits 16408 et 16535 ? Contrairement à ce qui est le cas pour 16408 et 16409, le ms. 16535 n’est pas une copie de 16408, ni son modèle. L’hypothèse suivante me paraît la plus probable. Dans le ms. lat. 16535, les textes concernés seraient antérieurs à ceux du ms. 16408. Notre bachelier, Etienne Gaudet, a assisté à une dispute à propos de la question citée plus haut et qui devait être l’une des questions courantes à la Faculté de théologie. Cette dispute faisait partie d’une cérémonie in aula, pendant laquelle un bachelier était mis à l’épreuve comme respondens. Etienne Gaudet écrit, d’après ses notes, un brouillon de la position du bachelier (ms. 16535, version A). Il en fait ensuite un résumé, tel que le candidat qui a passé l’épreuve doit le faire, mais il le laisse incomplet, car il ne résume pas la deuxième thèse et il supprime la conclusio principalis à la fin. Il ajoute par contre, dans le désordre, un certain nombre d’arguments et de réfutations qu’il a entendus durant la discussion (version B). En laissant un folio blanc (dans l’intention d’y ajouter éventuellement d’autres arguments ?), il procède ensuite à la mise au net d’une version longue de la positio, se basant en partie sur les arguments entendus pendant la discussion, mais il se limite à l’essentiel de la position, c’est-à-dire les trois conclusiones et leurs corollaria, en éliminant toute la partie introductive et tout ce qui concerne la cérémonie, y compris la conclusio principalis (version C). Plus tard, Etienne Gaudet doit lui-même jouer le rôle de respondens dans la dispute (aula) à l’occasion de la maîtrise de Guillaume de Fontfroide, à propos de la même question. Il fait une ébauche détaillée de sa positio, en utilisant sa documentation, à laquelle il reprend notamment les conclusiones et, en partie, les corollaires, mais il prend soin de les présenter différemment (ms. 16408, texte 1). Puis, il fait un résumé de ce texte, résumé dans lequel les citations sont très abrégées et les arguments sont souvent écrits sur une seule ligne (texte 2). Non content du résultat, il fait un autre résumé, encore plus abrégé, et dans lequel il ne se contente pas de copier littéralement le précédent : il change encore quelquefois des formules (texte 3). Ce texte, était-il destiné à être remis au maître qui dirigeait la dispute ou à servir d’aide-mémoire pour sa présentation durant cette dispute? La seconde explication me paraît la plus vraisemblable. Finalement, après la disputatio in aula, il reprend le résumé de sa positio qu’il avait écrit en préparation, très brièvement et en changeant légèrement sur certains points, et il le fait suivre par le rapport de la dispute (texte 4). Les quatre textes forment ainsi une documentation intéressante pour le traitement de cette question et la préparation d’un bachelier à son intervention dans une dispute solennelle. C’est la raison pour laquelle ils ont été copiés tous les quatre par le scribe du ms. 16409.

Thus, the close inspection of manuscripts can provide us with a deeper understanding of the circumstances in which the texts originated.

Commentaires récents