When studying a text, ancient, medieval or modern, close reading is of course necessary to understand the meaning and implications of every part of it. On the other hand, placing the text in its context is just as necessary for its correct understanding.

The editions of father Gauthier, of the Commissio Leonina, responsible for the editing of the works of Thomas Aquinas, are a fine example of this principle. That was the essence of my small talk during a gathering in honour of Louis Jacques Bataillon, in 2005, under the title “La Commission Léonine et l’histoire intellectuelle”. I quote a passage:

Saint Thomas d’Aquin

Avoir une bonne édition critique d’un texte de saint Thomas, que ce soit dans le domaine de la logique (je pense aux éditions des commentaires sur le Perihermeneias et les Analytica Posteriora), ou dans celui de l’éthique, de la politique ou d’autres disciplines encore, est d’une importance qui n’a pas besoin d’être soulignée ici. Et la qualité de ces éditions a été reconnue depuis longtemps. Je cite le même article de Bazán: « L’édition récemment publiée […] témoigne de la rigueur méthodologique, de la connaissance immense des sources de la pensée de S. Thomas, et de la vision d’ensemble du contexte historique qui ont été atteintes dans l’accomplissement du projet d’édition des Opera omnia ».

En effet, une bonne édition s’accompagne d’une bonne introduction et celles de la Commission Léonine sont d’une richesse rare. Elles constituent en soi des contributions fondamentales à l’histoire intellectuelle et à l’histoire des idées. Dans ces introductions, issues directement des analyses nécessaires pour établir le texte critique, on trouve, bien entendu, la description minutieuse de tous les témoins du texte ainsi que l’exposition de la critique textuelle; mais on y trouve aussi des chapitres consacrés aux sources de S. Thomas, tant sur le point de la traduction utilisée qu’en ce qui concerne les commentaires de ses prédécesseurs. Parfois, la ligne se prolonge même au-delà de S. Thomas: dans l’introduction à l’Expositio libri Posteriorum, René-Antoine Gauthier décrit aussi les commentaires qui ont à leur tour utilisé ce texte, des Questiones de Jacques de Douai, vers 1275-1280, en passant par quelques maîtres anonymes, Pierre de St-Amour et Gilles de Rome, jusqu’à Guilhem Arnaud, tout à la fin du XIIIe siècle. Notons aussi, dans la même introduction, le paragraphe consacré à l’Euclide latin, une source secondaire de Thomas, et aux trois œuvres par lesquelles ce dernier en a eu connaissance: l’Ars geometriae du Pseudo-Boèce, la traduction d’Adélard revue par Campano de Novare, et la traduction arabo-latine de Gérard de Crémone. Vous voyez quelle diversité de renseignements se cache dans ce qui se présente comme une simple introduction.

Introductions to critical editions giving detailed information about the intellectual and doctrinal context (although unhappily not very numerous) seem indeed a normal feature of the work of a medievalist as well as a mark of respect for colleagues.

Gersonides in context

The cover of an excellent book on Gersonides

Another situation in which providing the context seems at least useful is in studies concerning specific authors or topics. And this should be extended to other cultures. An example of this kind of cooperation between scholars studying different cultures is the volume edited by Colette Sirat, Sara Klein-Braslavy and myself under the title Les méthodes de travail de Gersonide et le maniement du savoir chez les scolastiques (2003, see List of publications, art. 44, 45, 46). The comparison between Gersonides’s work and the scholastic methods, specifically the disputation, was fruitful indeed. It provided a new insight in the intentions and methods of the famous Jewish scholar Gersonides, at the same time showing the influence of the scholastic methods outside the world of the universities.

In the same context, I later published with Colette Sirat an article on another feature of the work of Gersonides: the use of loci or logical topics. The article, under the title Droit et logique: Gersonide et les juristes Chrétiens, was published in 2008 (List of publications, art. 60). I quote the English abstract:

The principles according to which Gersonides (1288-1344) wanted to harmonise the biblical commandments and the jurisprudence of the Talmud are stated in the introduction of his commentary on the Torah: nine loci which he took very probably from a collection of juridical loci assembled by contemporaneous Christian jurists.

The jurists in turn found the source for this device in an old logical tradition going back to Cicero’s Topics. The use of loci loicales per leges probati (also called modi arguendi in iure) is already attested in the works of the doctores antiqui, the old masters of law living in the eleventh and twelfth century. It subsequently expanded widely during the following centuries. The practice concerns in fact the application of logical loci or modes of argumentation in a rhetorical and juridical context.

Popularity of texts

Another side of studying the context concerns the question of the public: for which readers the texts have been written? Enlarging this question, the organisers of a colloquium held in Zurich in 2016 under the title Habent sua fata libelli. Auswahlprozesse in der lateinischen Literatur des Mittelalters, raised the slightly different question how medieval readers selected the texts that seemed important or interesting to them, among the ever growing mass of available literature. I contributed with a paper entitled Sélection et popularité des auteurs dans les universités médiévales (see List of publications, art. 72). My topic was the question if and how the authors and texts on the program of the faculty of arts were selected, and why some authors became more popular than others. I reproduce the abstract:

This paper examines how the new authors whose works were taught in the university were selected and why some were more popular than others, mainly in the field of the faculty of arts. The massive arrival of totally new texts (Aristotle, Avicenna, Averroes, etc.) was welcomed and acclaimed, because they opened up new fields of knowledge. However, some of them became more popular than others, for instance Aristotle’s treatise ‹De anima›, because it offered a whole new system of the science of living beings. The number of manuscripts as well as the glosses showing their use can give us an idea of the degree of popularity of the various texts. The examination of manuscripts at the BnF (Paris) containing collections of Aristotelian texts on natural philosophy shows that the ‹Physica›, ‹De anima› and the ‹Parva naturalia› were much more studied than other texts. It seems that at the arts faculty the basic texts have imposed themselves rather than having been selected. Among the commentaries written by the masters some became more popular than others, for instance the commentary on the ‹De anima› by Adam of Bocfeld, because it presented a convenient synthesis of Aristotle’s thought. Some handbooks and compendia had an immense and immediate success, as the logical handbook called ‹Tractatus› of Peter of Spain and the astronomical treatise ‹De sphera› of John of Sacrobosco.

The question had not occurred to me before and I am grateful to the organisers, specifically to Carmen Cardelle de Hartmann, for inviting me. It is a topic that should be studied for the other faculties too, because it gives us a glimpse of the academic society in those times.

Jean de Meun and the Arts Faculty

The social and intellectual context may also be approached by taking a source from outside the academic community and studying the relations between them. This is what I tried to do in an article entitled Jean de Meun et la Faculté des arts (see List of publications, art. 73). Originally, the text was a contribution to a colloquium on Jean de Meun and his famous Roman de la Rose, organised in Paris in 2016. Here is the abstract:

Le but de l’intervention est de mieux cerner les liens qu’avait Jean de Meun avec la Faculté des arts de Paris, en comparant les sujets mentionnés par l’auteur dans la partie la plus ‘scolastique’ de son œuvre (la plainte de Nature) qui sont en rapport avec ceux enseignés à la Faculté des arts, et ce que nous savons de cet enseignement par des sources directes. Après une présentation rapide de la situation à la Faculté des arts de Paris à l’époque de Jean de Meun, on passe en revue les sujets en question.

Dans le premier quart de la plainte de Nature on trouve des thèmes bien connus comme celui de la chaîne des quatre éléments, le déterminisme des astres par rapport à la libre volonté, la question de la prédestination divine. Comme il a déjà été observé dans le passé, cette dernière question est discutée sous une forme qui ressemble à la dispute scolastique, dont on retrouve d’ailleurs le vocabulaire.

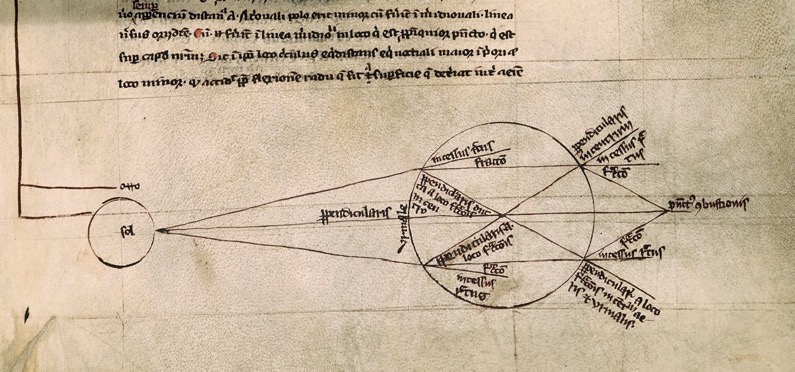

Dans la suite du texte, Jean de Meun, en la personne de Nature, aborde des sujets relatifs à la philosophie naturelle, en commençant par la météorologie. On trouve notamment une mention de l’arc-en-ciel et une discussion de l’optique, dans laquelle l’auteur cite nommément Aristote et Alhazen. Il a déjà été montré que la source de ce passage est probablement le traité De perspectiva de Roger Bacon, ce qui impliquerait que Jean de Meun était au courant de la production scientifique de son temps.

D’autres passages, par exemple ceux qui sont relatifs au sens commun ou encore aux comètes, semblent confirmer l’impression que Jean de Meun connaissait certains textes lus et commentés à la Faculté des arts. L’hypothèse qu’il y a suivi des cours est donc vraisemblable. Par contre, rien n’indique qu’il y ait enseigné.

L’impression que donne tout ce passage savant, comme d’ailleurs le reste du poème, est surtout celle d’un homme pourvu d’une large culture littéraire. Jean de Meun, après une jeunesse imprégnée par la lecture des auteurs classiques, a su opérer la synthèse des deux cultures, littéraire et scolastique, là où la Bataille des sept arts les avait opposées.

Un schema dans le De multiplication specierum de Roger Bacon, lu par Jean de Meun

Both approaches: the comparison with other cultures or with works in the vernacular, provide a wider picture of the context in which the medieval arts faculty should be considered.

Commentaires récents