The faculty of arts was a rich and little explored field. The idea of Louis Holtz to replace the old repertorium of Palémon Glorieux, La Faculté des arts et ses maîtres au XIIIe siècle, published in 1971 and containing many errors, by a new one that would include the whole Middle Ages, but would of course be limited to the arts faculty of Paris, had excellent results. It opened my eyes to the sheer number and interest of texts that were unknown to me before. It also meant a big enterprise, not as big as the dictionary of medieval Latin, but still a work of many years. And, as it was also a publication in alphabetical order, it assured a certain continuity (not least from the institutional point of view).

Thus I started to design the new repertorium, with the assistance of several friends, among whom Prof. Dr. L.M. de Rijk and Louis Jacques Bataillon. I decided to use the title Le travail intellectuel à la Faculté des arts de Paris: textes et maîtres in order to explain the ideological background of the work: intellectual history, not prosopography (that is the history of the intellectual activity at the faculty of arts, not of the personality and career of the authors). The central topic was which texts were read and taught, by which masters, not the biographical details of the masters. This decision was criticized, but also supported from the beginning. In my eyes the title has the merit to characterise the contents from the ouset, although in short, of course, I refer to it as ‘the repertorium’. The idea was also to include not only the works actually read during the lectures, but also the contemporary works in the same field to which the masters had access. For this purpose I designed three categories of entries, marked by the letters M for Master (teaching at the faculty of arts in Paris), S for Source (contemporary sources related to the disciplines taught there and known by the Parisian masters) and D for Doubtful (uncertain if they belong to M or S). After the first small fascicle, containing the masters whose names begin with A and B, I realised that there were many cases of authors not entitled to enter the repertorium according to our criteria, but still closely related. Thus I created a special category for the “Exclus”: 1. authors working on the disciplines of the arts, but outside the chronological limits (ca. 1200-1500); 2. those whose works are close to the milieu of the arts faculty without belonging to it (for instance the ars dictaminis); 3. those working in the field of the arts faculty in other places and probably not known in Paris; 4. those whose name is known to us, but of whose works we don’t have any manuscript or printed copy. The section containing the “exclus” was much expanded in later fascicles and can be used as a parallel source of information.

The fascicles became more extensive in the course of the years, partly because some of my correspondents of the international network provided ample material, especially Sten Ebbesen and Angel d’Ors (on the latter see below). After six fascicles, I began to feel that I would not be able to finish the work on my own. Luckily, I obtained some funds to engage a collaborator and from that time on I had the pleasure to share the work with Monica Brînzei (at the time Calma-Brînzei). We published the last three fascicles together. Of course, a supplement would have been useful, and even more, perhaps, an online edition, but as it is (8 fascicles), with all its shortcomings, the repertorium still renders many services, as I was often told in later years. (see List of publications, Books 8, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21)

Cover of the last fascicle of the repertorium

Articles on the Faculty of Arts

During the twenty years of work on the repertorium (ca. 1992-2012), I published a number of articles related to the faculty of arts, on various subjects: see List of publications, art. 7 (vulgarisation, on Marsilius of Inghen, a Dutch master of arts), 39 (on the place of music in the teaching of the arts faculty), 48 (on Dutch masters at the arts faculty of Paris), 61 (together with Louis Jacques Bataillon, on Langton and the beginning of the faculties in Paris).

A minor theme of my work on the faculty of arts consists in the academic practice of examinations and ceremonies. I treated this topic in three articles:

n° 26 Les règles d’examen dans les universités médiévales, published in a volume on the universities in the Middle Ages, in 1995;

n° 38 Une trace de la cérémonie de l’”inceptio” à Oxford vers la fin du XIIIe siècle, in a volume offered to Pavel Spunar, in 2000;

n° 55 Un exemple de la cérémonie de l’inceptio à Oxford au début du XVe siècle, in a volume in honour of Alfonso Maierù, in 2007.

The last two articles show the useful side of what is called in French “Mélanges”, collections of articles in honour of a distinguished scholar: apart from the homage, it allows the contributors to take up one of their themes of research and give particular examples.

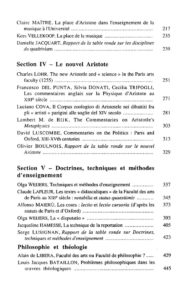

With Louis Holtz, I organised an international colloquium on the theme L’enseignement des disciplines à la Faculté des arts (Paris et Oxford, XIIIe-XVe s). For the proceedings, see List of publications, Collective Volumes, 7. I reproduce the table of contents:

Cliquez sur les images pour les agrandir

One of my articles related to the faculty of arts, a paper intended for a volume prepared in honour of Angel d’Ors, in 2014, has not been published, because it did not fit in the volume, which was published as an issue of the periodical Vivarium. In memory of my friend and colleague Angel d’Ors, and as it may be interesting for some scholars, it follows here in its original form: Spanish Scholars

Repertories of philosophical texts

Regarding more specifically the inventories of philosophical sources, I presented a talk on repertories of philosophical texts in Florence, invited by Claudio Leonardi, at the marvellous Certosa del Galluzo, where the S.IS.M.E.L. was lodged. Here is a scan of my notes:

Among the tools to find philosophical texts and their manuscripts mentioned in the notes for the paper above, the volumes of Lacombe listing the manuscripts containing Aristotelian texts and the repertory of Charles Lohr, Medieval Latin Aristotle Commentaries, are of course well known. Less known are the national or local repertories : Commentaria Medii Aevi in Aristotelem Latina, written by different authors with different presentations. In this series, prof. L.M. de Rijk and I published a small volume (61 pp.) on the few Aristotle manuscripts kept in Dutch libraries (see List of publications, Book 5). A more recent tool is the Repertorium Initiorum Manuscriptorum published by Jacqueline Hamesse (Louvain-la-Neuve 1997-2010), inevitably rather incomplete.

Already in those days, I could mention two online repertories, one limited to logical texts: Medieval Logical Manuscripts, a research project of L.M. de Rijk and E.P. Bos at Leiden University; the other an ambitious database encompassing not only Aristotle commentaries but also those on the Sentences, by Steven J. Livesey: COMMBASE: An Electronic Database of Medieval Commentators on Aristotle and Peter Lombard’s Sentences, which provides ample information about life, career and work of the various authors.

Since, the spectacular multiplication of electronic tools for finding texts makes one wonder if there is still time left to have a look at the texts themselves.

Commentaires récents